[07.02.22] Blog – How to deliver renovations to energy poor tenants: Greek and Estonian National Renovation Policy Improvements

By Eva Suba, Climate Alliance with the input of Marek Muiste, TREA and Christos Tourkolias, CRES

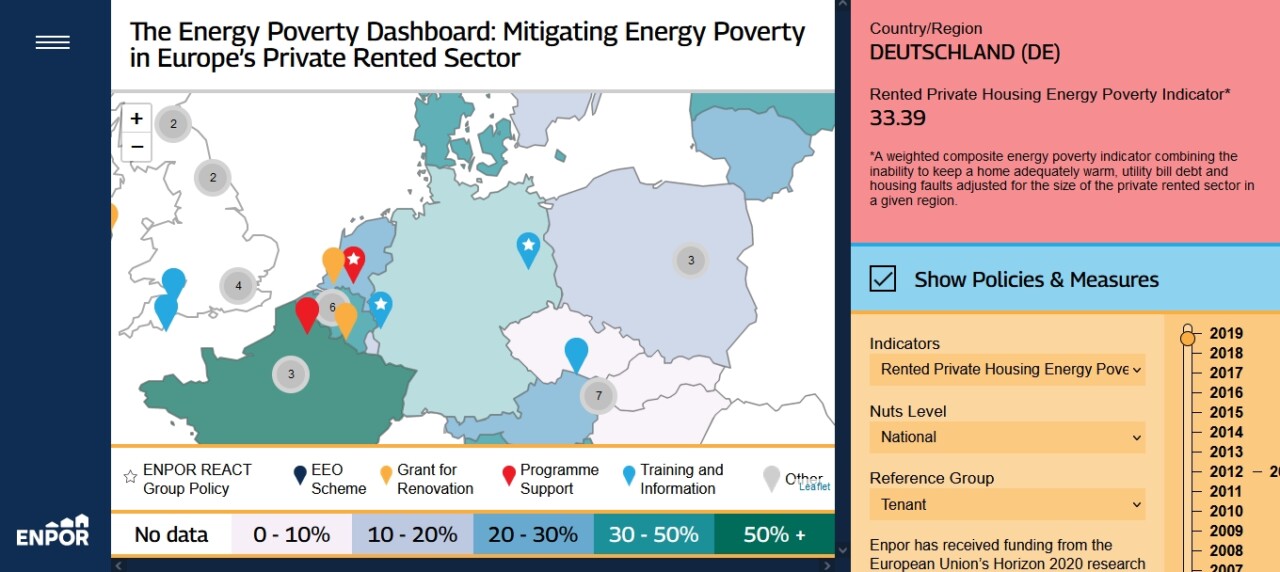

Living in energy poverty means for a lot of citizens facing social exclusion, degradation of quality of life and severe impacts on health. Policy makers and public administrators in various areas thus also need to face the consequences in housing policies, social policies support and public health systems. The concept of energy poverty however is fairly new to several national and local policy makers in various European countries. Recent spikes in energy prices targeted the attention of consumers and policy-makers alike on the looming shadow of energy poverty. For the first time in post-war Europe, energy prices raised in heights that increase the possibility of more and more households (even those who would count as middle-income families), may find themselves on the edge of vulnerability when it comes to affordable energy. The risk may be particularly high for vulnerable groups such as single female parents living in rental homes or elderly low-income tenants, especially in countries where a high share of the population lives in rental homes. While the number of people renting their homes or living in social housing across Europe varies (eg. Germany: 49,14 %, Austria 44,78%, France 35,98%, The Netherlands 31,12% of the population as of 2019 according to the Energy Poverty Dashboard), the risk for tenants facing energy poverty in the private rented sector should alarm policy-makers and public administration alike. The recently developed ENPOR Rented Private Housing Energy Poverty Indicator (REPI) shows, that policy-makers, decision-makers need to consider not only one of two, but the combination of various factors to understand the reasons causing energy poverty to be able to reduce it and mitigate its effects.

In developed economies, energy poverty occurs when households experience inadequate coverage of their essential energy needs at home (heating, cooling, lighting) and transport. Energy poverty originates from a combination of three factors: low household income, high energy prices and inefficient buildings and equipment. The ENPOR indicator REPI includes the share of people unable to keep their home adequately warm, the share of people reporting utility bill arears, the share of people reporting housing faults and the share of people living in the private rented sector. It will show higher value in cases where any of these values are higher, meaning that countries where energy poverty in the PRS is greater, and the size of the PRS is significant, will combine to yield an elevated score. Countries like Greece, Portugal, France, Ireland, Germany, which score relatively low on conventional energy poverty measures, record high values of the REPI (as of 2019 data).

In recent years, it was difficult to convince the stakeholders to allocate time, money, and effort into the policy development tackling energy poverty, not to mention energy poverty in the private rental sector. One of the major challenges associated with energy poverty is its multidimensional nature. It is a problem that includes both social aspects and technical aspects regarding energy efficiency. Since tackling the issue requires an interdisciplinary approach it often proves to be a challenge in implementing adequate measures, as experts from the fields related often lack practical access to the other.

The second challenge is due to the existing division of the labour and separation of the subjects in public administration. Especially overcoming structural problems like the lack of financial capacity among the private owners and renters can be challenging. Poverty and energy are topics under different administrations, having different formalities, institutional practices, and funding. Here, synergy effects could be used and interdisciplinary approaches are needed to be implemented. This process requires political will to set up plans at the level of public administration to become active in this direction.

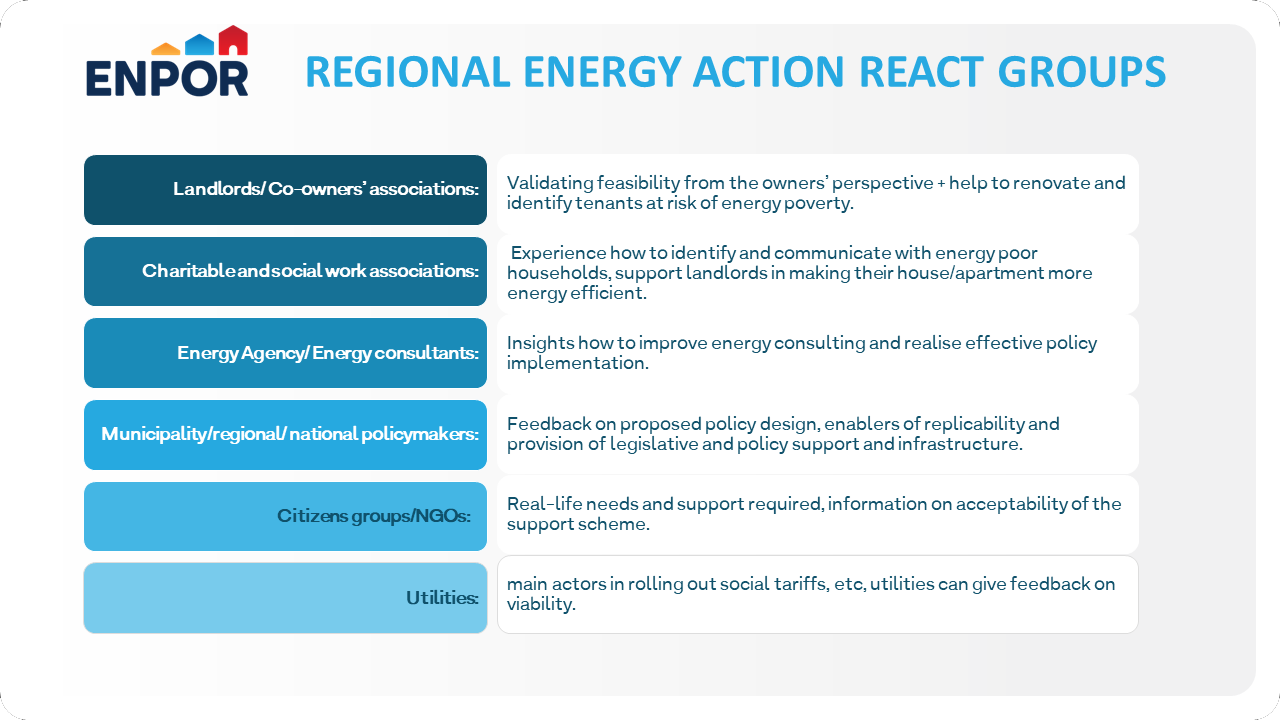

In the course of the ENPOR project, Regional Energy Action Groups (REACT) in 7 countries examine ways to improve 10 policies addressing energy poverty. These groups follow the ENPOR Stakeholder Engagement Strategy to involve relevant stakeholders in this process and will formulate policy improvement recommendations. At this point of time we give a short first glimpse of the policies and initial set of recommendation drafts in Estonia and Greece. More details regarding these and all ENPOR countries’ (beyond Estonia and Greece, REACT Groups are active in Austria, Italy, Croatia, The Netherlands and Germany) mid-term findings in the REACT Groups including the details of the policies, are detailed here.

Estonia: National Renovation Grant

The Estonian national renovation grant was established in 2010 as a public initiative under the Estonian financial institution KredEx that became a grant holder. It was meant to be a temporary measure for supporting the market uptake of the liberal retrofitting economy of a fully privatised Estonian housing market. Within the first 10 years of its operation, the grant helped to renovate 1,114 buildings that will reduce the emissions by 140,000 tons of CO2.

The shortcomings of the Estonian national renovation grant can be divided into three categories according to our observations:

- Financial shortcomings, such as heavy reliance on the financial capacity of the building associations and by this, the owners,

- Administrative shortcomings, such as the lack of stability, and

- Technical shortcomings, such as the support of partial renovations with only a limited effect on the energy efficiency.

With criteria for the loan applications, the banks are superimposing their own set of conditions and thus creating a barrier for the buildings’ renovations in the areas that do not witness the increase of real-estate value as an outcome of the retrofitting. With no way to meet the loan criteria, these areas are locked out of using the public grant and, because of this, are becoming the retrofitting dead-zones, further amplifying the regional inequity in living conditions and energy improvements. In 2020, the situation has been improved with providing a state financed loan service for the applications rejected by the private banks.

The following ideas and proposals were developed as an outcome of the co-creation process with the REACT group. These also go beyond the scope of the project and present general possibilities for improvement and possible measures for political decision-makers in Estonia.

1.Renovation capacity in regulations and legislation:

Renovation capacity itself should be a priority, instead of repairing one roof or façade, one should improve the whole building, the full renovation of historic buildings.

2.Increasing the capacity of the parties for participating in the renovation process, including:

including tenants into the decision-making process together with the owner of the rental apartment (or as its representative), Providing renovation information also for non-native speakers, Promoting wider use of digital tools in the housing association participation

3.Increasing renovation capacity with the help of the national renovation grant, including:

- Long term financing for the state renovation grant (min 10 years).

- Inclusion of energy poverty target groups into the national renovation grant and evaluate its impact to energy poverty.

- Creating additional measures for supporting the building associations lacking the renovation capacity in the process of full renovation.

- Supporting the cluster renovation, with the necessary simplifications for joint procurement and measures to improve the capacity of associations.

- Supporting the district-wide multi-building renovation,

- One Stop Shops: Establishing full package renovation consulting services in municipalities

- Setting up community agreements with organizations and associations that contribute to increasing the volume of full renovations of apartment buildings. The Community Agreement is an exciting engagement initiative initiated by the City of Tartu, which calls on organizations operating in the city to support the city’s sustainable goals.

Greece: national programme for the energy upgrade of residential buildings

Targeted policies are implemented in Greece in order to address the energy poverty phenomenon. The alleviation of energy poverty has been specified as an essential objective within the framework of the final National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP)[1], which was submitted in the end of 2019. The Action Plan for the Confrontation of Energy Poverty was prepared in September 2021 detailing policy measures so as to ensure the fulfilment of the specified targets within the NECP. Moreover, the definition of energy poor households was determined.

The Action plan established the conditions to identify households as energy poor in the case that both of the following conditions are simultaneously fulfilled:

- Condition I: The total final energy consumption of the household is lower than the 80 % of the minimum final energy consumption, which is required theoretically for covering the thermal needs.

- Condition II: The total normalized income of the household, based on the number of the household’s persons according to the equivalence scale of OECD is lower than 60 % of the mean income of all the households in Greece.

Nine policy measures have been integrated into the Action Plan for the Confrontation of Energy Poverty to fulfil the specified targets. These have been classified in three categories:

- Measures for the short-term protection of energy poor households

- Measures for the energy upgrade of the energy poor households’ buildings and the promotion of RES

- Μ4: Energy upgrade of the energy poor households’ building including the installation of RES systems

- Μ5: Provision of incentives to energy poor households within the framework of the Just Transition Plan

- Μ6: Provision of incentives to energy poor households within the framework of the EEOs

- Μ7: Provision of incentives to energy poor households within the framework of Energy Communities

- Information and awareness-raising measures

The first ENPOR pilot policy in Greece is the national programme for the energy upgrade of residential buildings. It is the continuation of the ‘Energy Savings at Home’ programme focused on energy poor households. The ‘Energy Savings at Home’ programme started in 2011 providing financial incentives to households, including low-income households, so as to replace the window frames and install shading systems, to install thermal insulation in the building envelope, including the flat roof/roof and ’pilotis’ and to upgrade the heating and hot water system. The financial aid consists of capital subsidy and low interest loans including the subsidy of the interest rate and the coverage of the energy inspections’ cost. The measure has continued until 2021 via the “Exoikonomo-Autonomo” programme after continuous improvements enabling the implementation of the most cost-effective interventions to improve the energy efficiency of the residential buildings.

The proposal for the case of the “Energy upgrade of buildings” programme, as resulted by the application of the co-creation process within REACT group meetings, foresees the inclusion of the tenants as a distinct social criterion, while the provided public aid must be calculated taking into account the shared benefits among landlords and tenants.

According to the proposed design a specialised benchmarking system will be developed taking into account specific energy and social criteria for the evaluation and ranking of the submitted applications. The energy criteria consist of the expected energy savings, the heating degree-days, the energy class or EPC of the building before the energy renovation, the construction age and the households’ income. The social criteria comprise the existence of long-term unemployed members, disabled members, children and single-parent families. It should be noted that a specific weight will be assigned to each criterion in order to calculate the final score of each submitted application separately. Moreover, a special provision for the rented buildings has been introduced foreseeing the provision of 40 % subsidy to the landlords. Finally, a dedicated portion of the foreseen public budget will be allocated to the energy poor households within the framework of the new programme fostering the implementation of targeted policies for tackling energy poverty in compliance with the targets of the Action Plan for the Confrontation of the Energy Poverty in Greece.

Another contribution of the co-creation process was the insertion of a targeted reference regarding the split incentive problem into the Action Plan for the Confrontation of the Energy Poverty within the measure M4, which refers to the energy upgrade of the energy poor households’ buildings in the period 2021-2030.

Read more about the ENPOR Policies: https://enpor.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ENPOR-D3.2.pdf

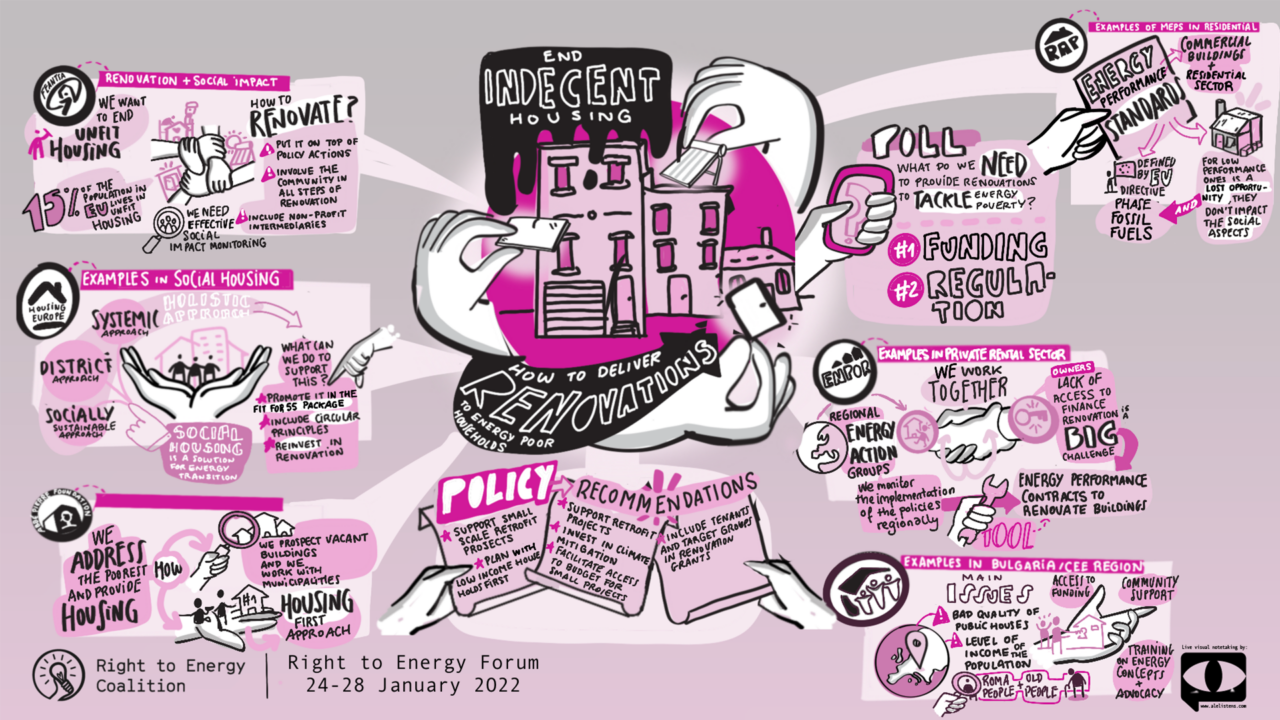

These recommendations were summarised in the Right to Energy Coalition’s 2022 Forum on 25th of January 2022 at the „End indecent housing: how to deliver renovations to energy poor households” session with 118 participants.

Watch the Recording of the session here:

[1] Source: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/default/files/el_final_necp_main_en.pdf